“THERE is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.” – Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

The above quote may seem an absurd way to begin an essay, but absurdity in The Walking Dead is the very idea I intend to explore here. To give a little more context, I must admit the Season 7 finale struck a chord with me. In particular I found Sasha’s role in the episode intriguing and thought provoking. This led me down a long line of characters in the last seven seasons who committed suicide, for various reasons. While it is true that the TV show more regularly dealt with suicide in the earlier seasons, it still remains a common theme in The Walking Dead. But why is this the case? Is it enough to say that people in this world simply don’t want to live anymore?

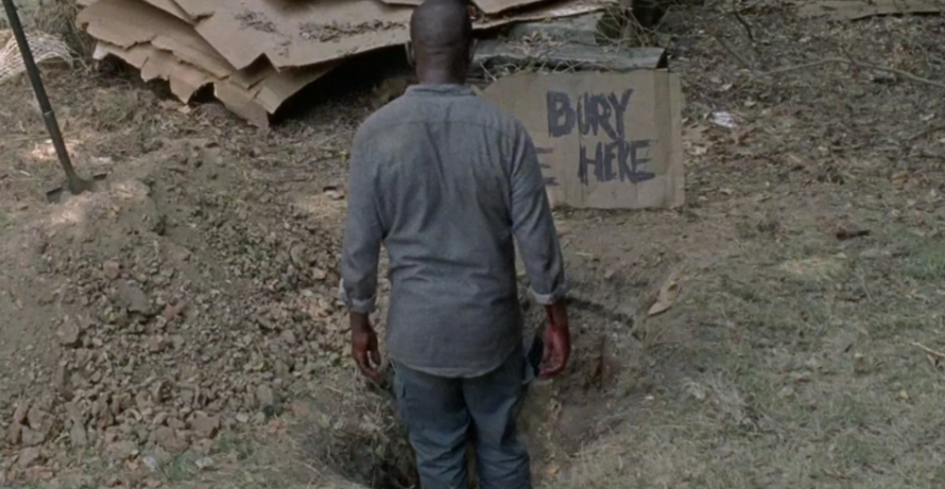

I imagine The Walking Dead as a kind of Absurdist drama, or a Theatre of the Absurd, in this regard:

Theatre of the Absurd: A drama using the abandonment of conventional dramatic form to portray the futility of human struggle in a senseless world.

The Walking Dead has always done a fantastic job of tearing away social structures, and using these deconstructions to explore human meaning and value in existentialist terms, making it both deeply philosophical and deeply relatable in a world that feels utterly surreal and absurd. And this is the gist of Albert Camus’ philosophy. What point is there to a life that has no objective meaning, that is essentially void of any value, and if there is no point to this life, why should we not kill ourselves? This sentiment is echoed most by the characters who stay behind in the first season, at the doomed CDC building. These characters gave up, seeing the futility of their futures. But then why do the other characters move on, and why do they keep doing so again and again?

I do not think it enough to argue that the survivors are simply the people that keep moving forward. To do this would reduce the complexities of their characters to animalistic survivalism. And this is where Camus and his Myth of Sisyphus come in. Sisyphus, for him, is not simply a doomed man with no future. Sisyphus is no longer bound by a hope for an eternity. He toils in the now. To some degree, I see Rick and his group in a similar light. They find themselves constantly pushing their rock to the top of the hill, only to witness it roll back down again. They struggle in seeming futility, and yet continue in absurdist fashion.

The absurd man says yes and his efforts will henceforth be unceasing. If there is a personal fate, there is no higher destiny, or at least there is, but one which he concludes is inevitable and despicable. For the rest, he knows himself to be the master of his days. At that subtle moment when man glances backward over his life, Sisyphus returning toward his rock, in that slight pivoting he contemplates that series of unrelated actions which become his fate, created by him, combined under his memory’s eye and soon sealed by his death. Thus, convinced of the wholly human origin of all that is human, a blind man eager to see who knows that the night has no end, he is still on the go. The rock is still rolling. — Albert Camus