There’s a certain charm that comes from visiting the Deep South in the spring and summer. The air is thick, humid and full of the aromas of fried foods and blooming flowers. Kudzu and Spanish moss wage war with one another from tree tops and phone lines to slowly swallow the old brick edifices of colonial and Antebellum buildings that still thrive along cobbled streets, now bustling in towering modern structures and architecture. The heritage and culture of an age otherwise lost to antiquity, swallowed by popular classics like Gone with the Wind is still alive and thriving and no tradition has survived better and more brilliantly than the ghost story.

In every major city from Memphis to Roanoke, Atlanta and beyond, you’ll find historical sites dating back to the colonization of North America, the founding of the nation and the pioneering period leading up to the Civil War. While each of these sites is rich in its own history, from the Lost Colony and the Atlanta Underground, to Cades Cove and Voodoo Village, most are as notable for their supernatural lore as for their actual historical value. I’ve made it a point over the years to visit some of these sites, touring cemeteries and historic sites, as well as my own urban exploration of some of the ruins of the Old South. Most recently, I ended up in Charleston, South Carolina.

For those of you unfamiliar with some of this southern port city’s more noteworthy historical accounts, it is home to the Citadel military academy, Fort Sumter, where the opening shots of the Civil War took place and Battery Park, so named for the batteries or mortars and cannons that more often than not repelled invaders and marauding pirates, including the infamous Blackbeard. Lesser known in paranormal circles than neighboring Savannah, Georgia, the city holds onto its dead in much the same way as its contemporaries. From beautifully curated cemeteries behind high stone and brick walls, replete with palm trees and masonry dating from the late 1600s, to times as recent as 2015, to crumbling facades re-purposed for modern life, there is no doubt that the dead remain strong in Charleston. Of all the sites and tours I wanted to go on, but failed, largely due to weather, I managed to go on a ghost tour of the Old City Jail.

The Old Jail was completed in 1802 to be an improvement upon the old Provost Dungeon that had been in use since the colonization of the Carolinas in the late 1600s. Referring to it as anything but a dungeon, however, is a far cry from the truth of the matter. Despite being an improvement as life in the United States began to move away from the public humiliation and abuse of the old Imperial legal system, it was no better. The “holding area,” what we’d think of as a general population in a modern county jail or federal prison, was a room not much larger than a single-car garage, where up to 40 prisoners were kept for weeks on end. The rounded room, with its single-slit window and loose board floors was practically a death sentence for many who entered. Then, there was no separation of prisoners based on factors of age, sex or severity of crime. Violent thugs were placed into the room with others accused of lesser crimes like petty theft and “fray making,” which was akin to catching a drunk and disorderly charge today. Often times, these lesser criminals would become victims of their cellmates and even the guards watching them who, in turn, had most likely been held there at some point in the past.

The prison was literally run by the inmates, in most cases. As if this wasn’t bad enough, the overcrowded holding cell was also home to the flogging harness affectionately called “The Crane of Pain” in the room’s center. Those sentenced to lashes from the cat-o-nine-tails were suspended by taught ropes until their arms and legs were out of joint, then beaten savagely in accordance with the law. Most died from the teeming pool of disease and filth in the cell.

In tiers above this cell, the more violent criminals, rapists, arsonists and murderers (or at least those accused of these things) were held. Most famous of these were Lavinia and John Fisher, who had been accused of highway robbery. We’ve all been gouged while visiting some place from out of town, usually on haunted walks and other tourist traps, but in the early 1800s, it wasn’t uncommon to find yourself beaten and even murdered by inn keepers and vagrants along the roads outside of town, who would take your life before stripping you of your worldly possessions. This was the accusation made against Lavinia and her husband, John, who spent nearly a year in the hellish confines of the Old Charleston Jail before being hanged. While she and her husband held to their innocence until the bitter end, while John went quietly to the Gallows Pole to be hanged, Lavinia, a rather demure and small woman, managed to assault several guards and was dragged fighting by five men to her death. Her final words, often misquoted, are as chilling as anything else you may read in this article. “If you have a message you want to send to Hell, give it to me and I’ll carry it!”

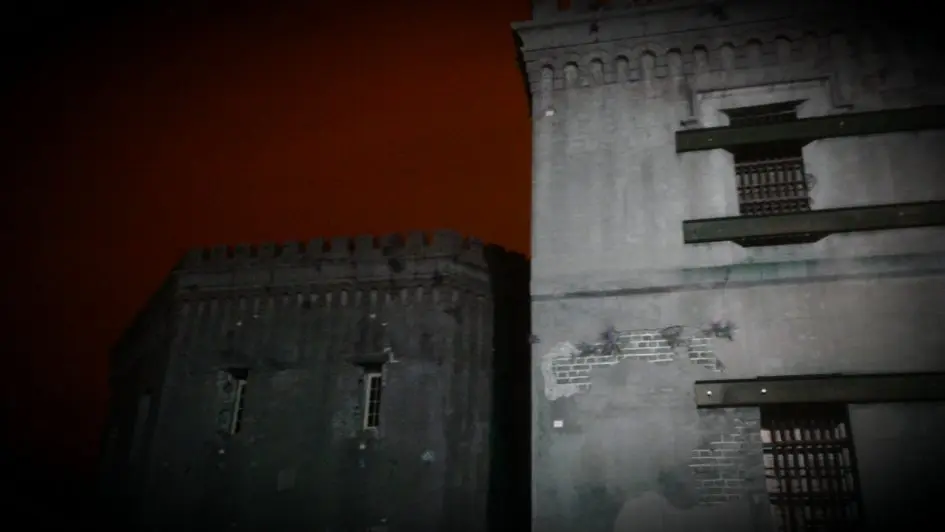

The sandblasted damage of overzealous workmen or the screaming face of a condemned woman?

For more than a hundred and thirty-seven years in operation, in conditions that were often seen as inhumane even in the day and ages of its use, the Old City Jail was home to petty criminals, pirates, slaves and prisoners of war, and the land it rests upon, as well as several hundred acres surrounding it, were used as a potter’s field. Thousands of men, women, and children died by hanging, beating, brutality and disease within the stone walls surrounding the jail, and the damnable and horrifying conditions and punishments forced upon them are all fodder for the legends that give rise to the haunted history of the location. It’s an integral part of haunted-house entertainment. Let me stop here and offer the following disclaimer:

I want to believe. I accept the possibility and plausibility of unknown forces and happenings that could be construed as paranormal activity in our world, as well as the reality that modern science as we know it may not currently be able to explain it. What follows is not meant in any way to impugn or belittle the lore, legends and reputed paranormal legacy of any of the locations or peoples mentioned.

OK, let’s call it what it is: Showmanship. Gathering after dark in the courtyard of the dilapidated Old City Jail, located between a clearly “gentrified” section of the city and a public housing project, a group of tourists has assembled to explore the decaying ruins of the dreadful place. We’re given an impassioned and informative brief on the bloody history and a tone is immediately established. Walking into the building, up narrow stairs and through small doors, we find an almost completely empty, poorly lit hovel that belies the former glory (or horror, depending on your view) of the structure. As we pass through each room, we experience a fraction of a percent of the unpleasant and uncertain existence that was faced within these walls, something begins to happen. We begin to empathize. Across the void of time and understanding, we feel a sense of dread and foreboding in the stories of suffering, in the claustrophobic darkness. The smell of other bodies pressed in close, the heat that has roasted the brick through the day, turned it into a kiln as our own heat raises the temperature another 10 or 20 degrees in the windless confines only makes the discomfort that much more palpable.

We feel eyes on us; we see images in the sandblasted fragments of wall and ceiling, in the odd reflections in the broken glass. Whether the place is haunted or not, we’ve awoken ghosts that will follow us through the rest of the evening. Even thinking about it now, as I write this article, I feel that eerie uncertainty as if someone or something is in the room looking over my shoulder. Later, I learned that the exterior of the building currently undergoing renovations is kept intentionally dilapidated to maintain the impression that the Old Jail is on its last legs and, other than a quick Google search and the words of the tour guide, there is little to no history presented in any form. You have to go in on your own, either before or after and really dig through the marrow if you want to know more than the atrocities that have given rise to the legends.

In the end, the ghost tours are little more than a way to make a buck peddling regurgitated, exaggerated and often times completely fabricated stories about historic sites that might otherwise fade into obscurity. If you’re looking for a good scare, something creepy without an asshole in a clown mask chasing you around with a chainsaw, then a ghost tour is the best thing for you. It gives that collective creep with the added bonus that you might just learn something by the time you get done.